Why Use Design of Experiments (DoE or DOE)?

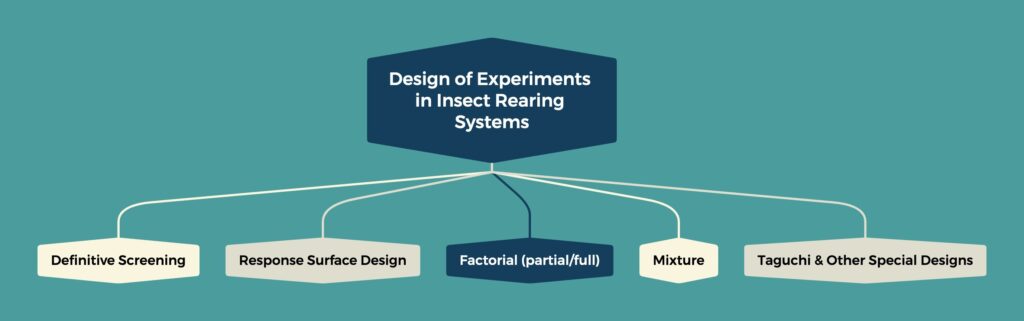

Instead of studying one factor at a time, rearing specialists can inquire about how multiple factors (or experimental variables) function within an insect rearing system. By doing DOE procedures, we can save on costly runs for our experiments; AND we can discover interactions between factors that we could not understand by using one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) experiments.

Some History of DOE in Engineering and Science and Specifically in Insect Rearing Science:

After struggling for almost 25 years (1979-2003) to develop artificial diets for various insects, I wrote the book Insect Diets: Science and Technology in 2003 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL) where I had stated that insect diet experts were burdened with experimenting with one factor at a time in their need to conform to “proper” experiemental design, which demanded a single factor or variable that was responsible for an outcome/effect/response.

Soon after my pronouncement about one factor at a time experiments, Dr. Steve Lapointe and his associates published a paper that was revolutionary for me and in my opinion for the entire community of insect rearing specialists: (Lapointe et al. 2008) where Lapointe and his team stated the reality that insect diets were mixtures and as mixtures could be treated with the statistical frameworks that described and helped analysis of complex mixtures and combinations of other interacting factors. Frankly, when I read Lapointe’s bold assertion that things could be done much more parsimoniously and effectively with multiple factor experiments, I was hurt and embarassed that my seemingly authoratative pronouncement was incorrect and naïve (though the authors were gentle with my assertion, I still felt a sting from having my authority challenged). After “licking the wounds of my pride,” I started to ask what was Lapointe talking about—doing experiments with multiple factors—using several variables in one set of experiments?

Reference: Lapointe, S. L., Evens, T. J. & Niedz, R. P. Insect diets as mixtures: Optimization for a polyphagous weevil. J. Ins. Physiol. 54,1157–1167 (2008).

In this historically important paper, Lapointe et al. used a response surface design to test multiple factors to improve a diet for Diaprepes a weevil that had proved difficult in prior efforts at diet development/improvement. The group showed that using the response surface design greatly simplified diet development, but beyond the importance of the accomplishment for a single insect the Lapointe group showed that DOE was a most valuable tool in diet development and for that matter rearing system development and improvement in general.

This set me into motion to try to learn how DOE worked and how I could apply it to my rearing/diet development goals. I will tell that story and my walk through the DOE system that I have been using: the JMP statistical package. Please see the following blog pages in the next few days….